Today, the data deluge that Big Data presents encourages a passivity and misguided efforts to get off the grid. With an “Internet of Things” ranging from our cars to our appliances, even to our carpets, retreating to our homes and turning off our phones will do little to stem the datafication tide. Transparency for transparency’s sake is meaningless. We need mechanisms to achieve transparency’s benefits. // More on the Future of Privacy Forum Blog.

Domestic Drones Should Embrace Privacy by Design

On Wednesday, the FAA held a forum to seek input from members of the public on the agency’s development of a privacy policy for domestic civilian drones. If the unmanned aircraft industry wishes to encourage the widespread societal embrace of this technology, suggesting that drones do not present privacy challenges and moreover, arguing that our current legal and policy framework can adequately address any concerns is counterproductive. // More on the Future of Privacy Forum Blog.

Civil Rights to Human Rights: The Legacy of Bayard Rustin

A year ago today, I helped organize a discussion on civil/human rights rhetoric in America at the Schomburg Center. The impetus for the program was the 100th birthday on civil rights legend Bayard Rustin, and with Occupy still fresh in minds, there was a great hook to discuss the need for greater social and economic equality. We brought together NYU’s Burt Neuborne, Columbia’s Kendall Thomas, and historian Ida E. Jones in a conversation moderated by Cathy Albisa, the executive director of the National Economic and Social Rights Initiative. While the full event was two hours long, I made a quick highlight reel.

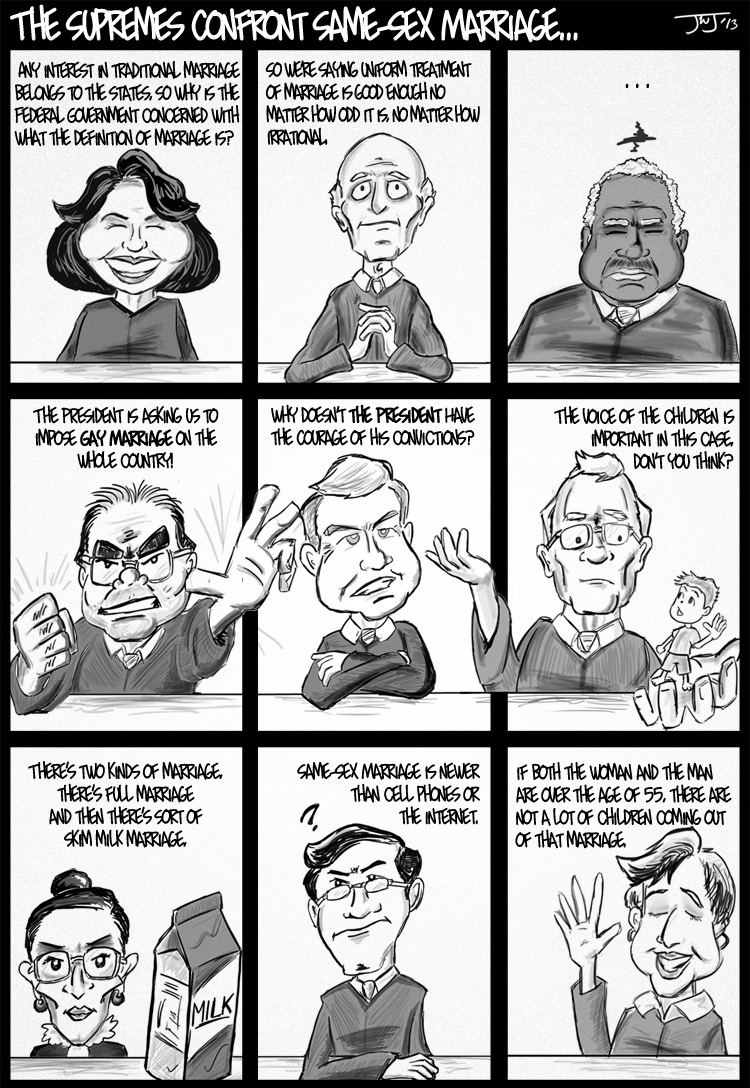

The Supreme’s Take on Same-Sex Marriage

I didn’t have much time this week to gather my thoughts on the Supreme Court’s handling of the Proposition 8/DOMA arguments (yet I did find time to doodle caricatures of the justices), but I thought some of the quotable highlights coming out of oral arguments were pretty priceless.

Keeping Secrets from Society

While the first round of oral arguments surrounding gay marriage was the big event before the Supreme Court today, the Court also issued a 5-4 opinion in Florida v. Jardines, which advances the dialog both on the state of the Fourth Amendment and privacy issues generally. In Jardines, the issue was whether police use of drug-sniffing dog to sniff for contraband on the defendant’s front porch was a “search” within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. By a slim majority, the Court held that it was.

This is what our protection against “unreasonable searches” has become: a single-vote away from letting police walk up to our front doors with dogs in order to see if they alert to anything suspicious. What I think is even more alarming about the decision is how little privacy was discussed, let alone acknowledged. Only three judges–curiously, all three women–recognized that the police’s behavior clearly invaded the defendant’s privacy. The ultimate holding was that bringing a dog onto one’s property was a trespass, and the Fourth Amendment specifically protects against that. But while defaulting to a property-protective conception of the Fourth Amendment has the virtue of “keep[ing] easy cases easy,” as Justice Scalia put it, it ignores that nuanced reality that the Fourth Amendment was designed as a tool to obstruct surveillance and to weaken government.

The dissent, meanwhile, was ready to weaken the Fourth Amendment even more. While this case was in many ways directly analogous to a prior decision, Kyllo v. United States, where the Court restricted the use of thermal goggles to inspect a house, the dissenters made the alarming assertion that “Kyllo is best understood as a decision about the use of new technology.” What makes that rationale scary is that Kyllo included the unfortunate invocation that whether or not government surveillance constitutes a search is contingent upon whether or not the technology used is “a device that is not in general public use.” This creates the not only the possibility but also the incentive to use technological advances to diminish the Fourth Amendment’s protection. It creates a one-way ratchet against privacy.

I am not the first person to suggest that the Supreme Court’s Fourth Amendment jurisprudence is utterly incoherent. I particularly enjoy the description that our Fourth Amendment is “in a state of theoretical chaos.” Last year, facing a case where the government attached a GPS unit to a car, tracked a suspect for a month, and never got a warrant, the Court unanimously concluded this violated the Fourth Amendment. That was great. More problematic, the case produced three very different opinions, that could not even cleanly divide along ideological lines. What it boils down is this: we are a serious privacy problem in this country.

And while its easy to point a finger at a power-hungry government, the blame rests with us all. We have been quick–eager even–to give up our privacy, particularly as we have embraced a binary conception of privacy. We either possess it, or our secrets our open to the world. We have been conditioned to think our privacy ends when we walk out the front door, and now we live in a world where nothing stops anyone from looking down on everything we do from an airplane, a bit lower from a helicopter, and, yes, soon even lower from a drone. We have no expectation of privacy in our trash anymore.

Just look at Facebook! Facebook isn’t even a product–it’s users are the product. Vast treasure troves of personal data flows into the business’ coffers, and it wants more. As The New York Times reported today, Facebook’s data-collection efforts extend far beyond its mere website. Facebook doesn’t even stop when you leave the internet. But worry not, says Facebook, “there’s no information on users that’s being shared that they haven’t shared already.”

That’s certainly true, but today it’s being aggregated. The data freely available about each and every one of us could, as The Times put it, “leave George Orwell in the dust.” Private companies collect “real-time social data from over 400 million sources,” and Twitter’s entire business model depends upon selling access to its 400 million daily tweets. Our cars can track us, and just today I saw the future of education, which basically involves knowing everything possible about a student.

I’m hesitant to quote Ayn Rand, but since an acquaintance shared this sentiment with me, it has dwelt in my mind:

Civilization is the progress toward a society of privacy. The savage’s whole existence is public, ruled by the laws of his tribe. Civilization is the process of setting man free from men.

Perhaps our collective future is, as Mark Zuckerberg posits, destined to be an open book. Perhaps Google CEO Eric Schmidt is right when he cautions that “[i]f you have something that you don’t want anyone to know, maybe you shouldn’t be doing it in the first place.” I am certainly not immune to oversharing on the Internet, and for whatever my privacy is worth, I don’t really have anything to hide. But that’s not the point. Before anyone embraces a world where the only privacy that exists is in our heads, I would suggest reading technologist Bruce Schneier’s rebuttal:

For if we are observed in all matters, we are constantly under threat of correction, judgment, criticism, even plagiarism of our own uniqueness. We become children, fettered under watchful eyes, constantly fearful that — either now or in the uncertain future — patterns we leave behind will be brought back to implicate us, by whatever authority has now become focused upon our once-private and innocent acts. We lose our individuality, because everything we do is observable and recordable.

Of course, as my boss describes it, Adam and Eve’s flight from the Garden of Eden had less to do with shame and more to do with attempting to escape the ever-present eye of God. Some would suggest we might have been better off in that idyllic paradise, but I much prefer to keep a secret or two.

ACS Law Talk Episode 11: The Future of LGBT Equality

After many months, my former employer has posted an interview I conducted with Nan Hunter, an associate dean and constitutional law scholar at Georgetown Law Center, and Nancy Polikoff, a professor of law and an expert on sexuality and the law. To mark the Supreme Court’s hearing of two cases impacting same-sex marriage, I spoke to the pair by phone to preview the arguments and what legal question comes next for the LGBT community.

Is Big Brother Getting Into Our Cars?

In the public relations battle between The New York Times and Tesla over the paper’s poor review of Tesla’s Model S electric car, the real story may be the serious privacy issues the whole imbroglio demonstrated. After The Times’ John Bruder wrote a less-than-flattering portrayal of his time with the Model S, Tesla Motors CEO Elon Musk challenged the review using information provided from the vehicle’s data recorders. In the process, Mr. Musk revealed that “our cars can know a lot about us,” writes Forbes’ Kashmir Hill. For example, Mr. Musk was able to access detailed information about the car’s exact speed and location throughout Bruder’s trip, his driving habits, and even whether cruise control had been set as claimed.

“My biggest takeaway was ‘the frickin’ car company knows when I’m running the heater?’ That’s a bigger story than the bad review,” gasped one PR specialist. Indeed, our cars are rapidly becoming another rich source of personal information about us, and this presents a new consideration for drivers who may be unaware of how “smart” their cars are becoming. Connected cars present a bountiful set of bullet points for marketers, but whether consumers are being provided with the necessary information needed to understand the capabilities of these vehicles remains an open question.

And it is not just car companies that will possess this wealth of information. Progressive Insurance currently offers Snapshot, a tracking device that reports on drivers’ braking habits, how far they drive, and whether they are driving at night. Progressive insists the Snapshot program is neither designed to track how fast a car is driven nor where it is being driven, and the Snapshot device contains no GPS technology, but the technological writing is on the wall. A host of marketers, telcos, insurers, and content providers will soon have access to this data.

In the very near future, parents will easily be able to track their teenagers driving in connected cars. Assuming cars permit their drivers to violate traffic rules, it may be impossible to actually get away with risky driving habits. Telcos increasingly find cars to be a lucrative growth opportunities. “[Cars are] basically smartphones on wheels,” AT&T’s Glenn Lurie explains, and indeed, many automakers see smartphones as an integral part of creating connected cars.

While we continue to grasp with the privacy challenges and data opportunities presented by smartphones, we have only just begun to address the similar sorts of concerns posed by connected cars. In fact, privacy concerns have largely taken a backseat to practical hurdles like keeping drivers’ eyes on the road and more pressing legal concerns such as liability or data ownership. Indeed, at the last DC Mobile Monday event, the general consensus among technologists and industry was that consumers would willingly trade privacy if they could have a “safer,” more controlled driving experience. Content providers were even quicker (perhaps too quick) to suggest that privacy concerns were merely a generational problem, and that younger drivers simply do “not think deeply about privacy.”

That may be true, but while industry may wish to treat our vehicles as analogous to our phones, it also remains true that the average consumer sees her car as an extension of her home. While the law may not recognize this conception, industry would be wise to tread carefully. OnStar’s attempt to change its privacy policy in 2011 proves illustrative. OnStar gave itself permission to continue to track subscribers after they had cancelled the service, and to sell anonymized customer data to anyone at anytime for any purpose. The customer backlash was brutal: “My vehicle’s location is my life, it’s where I go on a daily basis. It’s private. It’s mine,” went one common sentiment.

A recent article in The L.A. Times wondered whether car black boxes were the beginning of a “privacy nightmare” or just a simple safety measure. The answer likely falls somewhere in between, and if the Tesla episode reveals anything, it is that the striking the proper balance may be more difficult than either privacy advocates or industry expect.While Mr. Musk had a wealth of data at his disposal and Mr. Bruder had only a book of observations to counter that data, neither party has been able to provide a clear account of Mr. Bruder’s behavior behind the wheel. For example, what Mr. Musk termed “driving in circles for over half a mile,” Mr. Bruder claimed was looking for a charging station that was poorly marked. Technologist Bruce Schneier cautions that the inability of intense electronic surveillance to provide “an unambiguous record of what happened . . . will increasingly be a problem as we are judged by our data.”

Most everyday scenarios presented by connected cars will not produce a weeks long dispute between a CEO and a major newspaper. Instead, Schneier notes, neither side will be able to spend the sort of time and effort trying to figure out what really happened. Certainly, consumers may find themselves at an informational disadvantage. In the long term, drivers may be willing to trade their privacy for the benefits of an always connected car, but these benefits need to be clearly communicated. That is a discussion that has yet to be had in full.

Rural Minority Is a Vast Landed Majority

In an anecdote-filled piece on Republican obsolescence by Robert Draper in The New York Times Magazine, Draper discusses the results of a focus group of average Ohioans. When asked to describe the Republican brand, the following terms were generated:

When Anderson then wrote “Republican,” the outburst was immediate and vehement: “Corporate greed.”“Old.”“Middle-aged white men.” “Rich.” “Religious.” “Conservative.” “Hypocritical.” “Military retirees.” “Narrow-minded.” “Rigid.” “Not progressive.” “Polarizing.” “Stuck in their ways.” “Farmers.”

A number of those terms fit easily together, and I was struck instantly by the last term: “Farmers.” It’s no surprise that the Republican Party has an increasingly rural base.

Unfortunately for our ever-urbanizing country (and fortunate for our rural minority), the fruited plains and vast open “flyover country” that Republicans dominate affords them out-sized political power despite their dwindling numbers. While Democratic House candidates received more than 1.4 million votes than their Republican counterparts, they still face a thirty-some seat disadvantage in the House. Their Senate majority rests largely on Republican candidates that were . . . confused about rape. Combined with well-timed gerrymandering, the result is that Republicans have “drawn themselves into a durable House majority,” but one that is elected by “an alternate universe of voters that little resembles the growing diversity of the country.”

While the country has long trumpeted majority rule, Republican political power is the beneficiary of the powerful protections given to the minority in our Constitution. Instead, what the Constitution rewards political power to a landed majority. Since the Founding, agrarian America has been bolstered by structural guarantees such as the Electoral College and, yes, the long-stricken Three-Fifths Clause.

This made sense in Eighteenth Century when the American populace was widely dispersed throughout the former colonies. In fact, in 1790, at the time of the first Census, nearly 95% of Americans lived in rural areas. By 1900, this percentage had declined to 60%, but still, ensuring the political dominance of rural America still made sense. Today, rural America accounts for only 16% of the total population.

Republicans have embraced this 16% of the population to the country’s detriment. Certainly political polarization impacts the Democratic Party as well, but because Republicans can still have substantial national political power while representing a shrinking part of the country, the United States’ political development is stunted. Obviously, many parties instead see this state of affairs as an appropriate check on fluctuating democratic impulses. That notion may well be true in some circumstances, but because our politics has become perpetually locked into a two-party system, rural domination has unduly warped our political discourse. We have a party in lockstep with “conservative” rural interests against a broad base of “Democrats.”

As the Republican base has shrunk, the Democrats have become a big tent party. This creates its own set of problems: I was talking to a member of the Maryland state legislature, a state that’s utterly dominated by Democrats, and he bemoaned the single-party rule that’s spreading to more and more states. ”We should have Democrats versus Greens, and Greens could well represent farmers,” he said.

Instead, farmers are trapped with Republicans, and Greens are trapped with Democrats, and America suffers as a result. Our political discourse demands that we disconnect the landed majority from the trappings of political power. Some of this made sense at our Founding. It no longer does.

The High Costs of Cheap Drones

Three weeks into the new year, and the United States has already launched eight drone strikes across Pakistan and Yemen, killing 50 people. Among those killed was Maulvi Nazir, a Taliban leader in tribal Pakistan. While Nazir’s death has been portrayed as another in the long line of successful strikes against militants who may threaten America, it also has demonstrated the collateral damage that comes with our secretive drone war. Thousands of Pakistanis took to the streets in protest after Nazir’s death, denouncing the United States, and senior Pakistani security officials worry his removal will only increase violence and instability in the region.

Our embrace of drones has changed how the United States weighs the costs and benefits of waging war. Drones are cheap and effective, so much so that they make it easy for government officials and the American public to forget the sacrifices and consequences that come with using lethal force against another nation. As the United States increasingly relies on drone warfare, it is past time to have a serious public discussion about whether drone strikes are to be the exception or the rule. A recent report from the Council on Foreign Relations concludes that drone warfare presents four pressing problems: its foreign policy implications, unknown number of civilian casualties, lack of transparency or effective oversight, and unresolved legal questions. Whatever benefits our drone strikes may have, each of these issues raises serious concerns about the wisdom of relying on drones as a regular tool of war.

Former government officials and policymakers have voiced concerns that the United States is using drones as a crutch rather than developing a serious long-term strategy to combat international terrorism. In an interview Monday, retired General Stanley McChrystal, who developed the U.S. counterinsurgency strategy in Afghanistan, cautioned that drone warfare produces “resentment . . . much greater than the average American appreciates. They are hated on a visceral level, even by people who’ve never seen one.” And for good reason—a study last fall by NYU and Stanford law schools revealed with vivid detail how the constant presence of drones has terrorized the civilian communities over which they patrol.

Critics were quick to contend that the study had a small sample size, but unfortunately, that reflects one of the biggest problems with our use of drones. Hard data is difficult to come by. It may be true that drone warfare produces fewer civilian casualties, but there is no way to know at present. We cannot even be certain how many drone strikes have occurred. Data aggregated by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism suggests that somewhere from 2,562 to 3,325 people in Pakistan alone were killed by drones between June 2004 and September 2012. Headlines suggest a steady stream of successes in killing militants from above, but “militant” has been so broadly defined by the Obama administration as to include any military-age male.

The standards that guide when we can target these so-called militants can amount to nothing more than the CIA’s belief that an individual is engaged in a pattern of suspicious behavior. In fact, there are very few clear guidelines governing America’s use of drones, or if there are, the government refuses to say. On the very same day Nazir was killed in Pakistan, a U.S. federal court denied a request by the American Civil Liberties Union andThe New York Times to force the Obama administration into revealing the legal basis for its targeted killing program. Lamenting the “Alice-in-Wonderland nature of this pronouncement,” the court conceded it was caught in a “paradoxical situation” and a “veritable catch-22.” But like United Nations special rapporteurs and members of Congress who had tried in the past, the court was unable to lift the administration’s veil of secrecy. Whatever legal justifications exist for our use of drone strikes, the administration refuses to disclose them, and our drone warfare program remains officially classified.

Absent any meaningful oversight or public discussion it is impossible to determine whether our use of drone strikes has been either effective or legal. A tremendous disconnect exists between American decision-makers and the people in Pakistan, in Somalia, and in Yemen who feel the actual impact of our drone strikes. The capacity of the United States to wage war without placing a single soldier in harm’s way has made us blind to the growing chorus of people whose lives we have taken and societies we have destabilized all in the name of more efficient war. President Obama began his presidency with promises of openness and transparency, and he was elected with a mandate to bring sanity to the fight against al Qaeda and the Taliban. He should begin the new year and his second term by reevaluating whether drone warfare accomplishes either.

Space-Shifting Ruling Hampers Fair Use

Last month, Judge Richard Posner called on Congress and the courts to reform our broken copyright system. One of the most severe problems, he noted, is our increasingly narrow understanding of what constitutes the “fair use” of copyrighted works without a license. The boundaries of fair use have always been tricky to navigate, but as Judge Posner argues, it is “not widely recognized . . . that a narrow interpretation of fair use can have very damaging effects on creativity.”

The fundamental problem is a failure to understand what the purpose of copyright protection is. According to Kevin Smith, who answers copyright questions at Duke University, content industries now assert that “copyright exists to support their businesses, so any new way they find to extract a little extra money from the rights they hold should be endorsed and protected by the courts.” In a recent essay, John Mellancamp bemoans how the internet has ruined artists’ “gravy train” that permitted a song writer to depend on income from “one or two hit records 10 or 50 years ago.” But copyright was never intended to serve as welfare to artists; instead, the aim of the Copyright Clause is simply “[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts.”

In short, the copyright monopoly is intended to be limited. It presents no affirmative obligation to protect future potential revenue streams that exist solely for the benefit of content industries. Fair use exceptions are essential to ensure that our copyright regime can produce the wider public benefits for which it is designed. Unfortunately, while the boundaries of fair use remain often untested or ignored, copyright law remains beholden to restrictive and cumbersome rules established by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

Passed in 1998, the law has become an albatross on the larger body of copyright law. Case in point: the Library of Congress’ triennial review of 17 USC § 1201(a)(1)(A). In a misguided effort to combat piracy, the DMCA broadly prohibits efforts to “circumvent” digital rights management schemes. However, Section 1201(a)(1)(C) directs the Librarian of Congress and its Register of Copyrights to evaluate whether circumvention limitations adversely restricts the ability of individuals to make non-infringing uses of copyrighted works. It provides for public comment and review every three years.

In October, the fifth triennial review produced a new series of five exemptions to the DMCA’s circumvention prohibition:

[quote author=”Author” style=”normal” color=”#000000″] For the next three years, you’ll be allowed to jailbreak smartphones but not tablet computers. You’ll be able to unlock phones purchased before January 2013 but not phones purchased after that. It will be legal to rip DVDs to use an excerpt in a documentary, but not to play it on your iPad. [/quote]

“None of these distinctions makes very much sense,” Ars Technica’s Timothy Lee concludes. While the schizophrenic rules on jailbreaking and unlocking smartphones drew the most headlines, it is the final exemption – DVD-ripping – that demonstrates how absurd and arbitrary the current process is.

DVD-ripping, like CD-burning, facilitates what is termed “space shifting,” or moving a single file for use on one medium to another. Record companies, including the RIAA, have long agreed that this sort of activity is completely legal, and Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.), who sits on House Subcommittee on Intellectual Property, Competition, and the Internet, has explained that making digital copies is “a-okay.” He even went so far as to cite ripping a DVD in order to play a film on your iPad as a good example of an acceptable personal use.

In its recent review, the Register of Copyrights and the Librarian of Congress dismissed the notion that space shifting facilitated fair use. Further, in order to deny any exemption, the pair relied upon the fact that no court has yet ruled that space shifting constitutes fair use. As Lee explains, this produces a classic Catch-22. “To get such a ruling, someone would have to rip a DVD, get sued in court, and then convince a judge that DVD ripping is fair use. But in such a case, the courts would probably never reach the fair use question, because—absent an exemption from the Librarian of Congress—circumvention is illegal whether or not the underlying use of the work would be a fair use,” he writes. Beyond dismissing any fair use rationale, the Register of Copyrights also was concerned that space shifting could “adversely affect the legitimate future markets of copyright owners.”

Smith insists that a broad understanding of fair use is essential to ensure copyright law serves its primary public purpose. “If some private businesses can no longer survive in the new environment, that is not the primary concern of the courts, and certainly no reason to reshape the law,” he writes. For the Library of Congress, however, protecting the future markets of content industries and providing a gravy train for copyright holders remains paramount to ensuring the DMCA advances the public aim of copyright law.

While the Library’s current interpretation will restrict both competition and creativity, the public’s next opportunity to question the absurdity and arbitrariness of the Library of Congress will come in late-2015—unless Congress or the courts step in.